Thomas is an associate professor of psychology at Hope College.

There is a growing consensus among pediatricians, psychologists and educators that the youth are not ok. But the absence of mental illness is not the same as well-being. The real goal should be to raise youth with lives of purpose, internalized values and strong relationships, what psychologists call “flourishing.” Values of honor, service and self-sacrifice are inspirational and should be a part of a solution against youth languishing. Revive the dialogue around character education.

Character education systematically teaches ethics and virtuous habits such as gratitude, honesty and social responsibility. Over the past 30 years, research on moral development grew much faster than other psychology subdisciplines and became more diverse and interdisciplinary. When school-based character education is prioritized, it improves conflict resolution and moral reasoning and strengthens relationships. In sum, researchers know more than ever about evidence-based practices in character education. Yet policies and curricula emphasize intellectual and performance virtues (e.g., curiosity and determination) over moral or civic ones (e.g., honesty and service).

The Department of Education (see here, here and here) hasn’t mentioned the words “character,” “virtue,” “moral” or even “justice” in the last two strategic plans, covering 2014 through 2022. The last mention of character in a Department of Education strategic plan was the one from 2002-07, in which one of the six goals was to “develop safe schools and strong character.”

Character education isn’t prioritized. The Department of Education’s own “What Works” clearinghouse hasn’t tracked character interventions for 15 years. A current search for character or moral development in that database will find outdated reports and broken links or sources focused on “grit” and “growth mindset.”

Browsing through the standards across 50 states, few states explicitly prioritize virtues beyond self-interest. Researchers have called this avoidance moral phobia – when administrators and policymakers carefully side-step ethical language and pivot to social skills. State legislatures have paid increasing attention to “personal success skills,” “soft skills” or “non-cognitive skills.”

Developing social and emotional competence is indispensable in schools. It is also insufficient. If children are taught soft skills because it will make them feel better or be smarter, they won’t have the moral fiber necessary for complex ethical decision-making.

Rugged individualism is at its worst when it can only endorse self-centered virtues such as curiosity and confidence.

Perhaps this shift is rooted in a pseudo-psychology assumption that low confidence and self-esteem are the roots of all evil – they are not. Or maybe the shift away from character education is because schools are not supposed to impose personal moral values. Trying to remove morality from education is a fool’s errand. Children are always learning.

It is possible to develop social skills without fostering moral values of care and justice, and that’s bad news.

- Bullies can be confident.

- Corrupt politicians can have grit.

- Serial killers can have a growth mindset.

- But raising socially competent a--holes is not education’s goal; at least it shouldn’t be.

Character education in the United States had a renaissance in the 1990s with the Aspen Declaration, a resolution created by scholars, ethicists, and educators because people “do not automatically develop good moral character.”

Teaching character may address many of the problems experienced today. I work with a team of researchers developing school interventions across 60 Brazilian schools. Our work shows that socio-emotional learning is a powerful precursor to the virtue of social responsibility. Children who endorsed higher levels of social responsibility were the least likely to behave aggressively towards their peers. This likely happens because the intervention fosters stronger school relationships and indirectly promotes a more fair and just environment.

A values-based intervention among children in Canadian schools using moral virtues, role models and community partnerships had faster declines in aggressive behaviors compared to children from control schools. That intervention systematically integrated community leaders, students, parents and educators, so the children had a unified language around virtues. Other interventions have found that increased time spent in small-group discussions around moral values improves adolescent moral reasoning compared with control groups.

Character education improves integrity, compassion, educational attainment and problem-solving. It also reduces anti-social behavior, a growing public concern.

Experts know how to implement and assess character education; it can be integrated into the school curriculum. Social studies classrooms can be a springboard to discuss harm, justice and social norms. STEM disciplines can motivate truth-seeking and intellectual humility.

This isn’t to say that character education gets no attention. Many individual teachers put much thought and effort into developing the moral character of their students. Character.org, a nonpartisan organization of educators, researchers, and business and civic leaders, helps schools implement character education. This year, it has certified over 50 schools, but that’s a small percentage of the thousands of schools in the country.

Marvin Berkowitz, a renowned character education expert, said that if we want a more just, equitable, and compassionate world we must educate more just, humane, ethical people. That’s what character education does; we need it now more than ever.

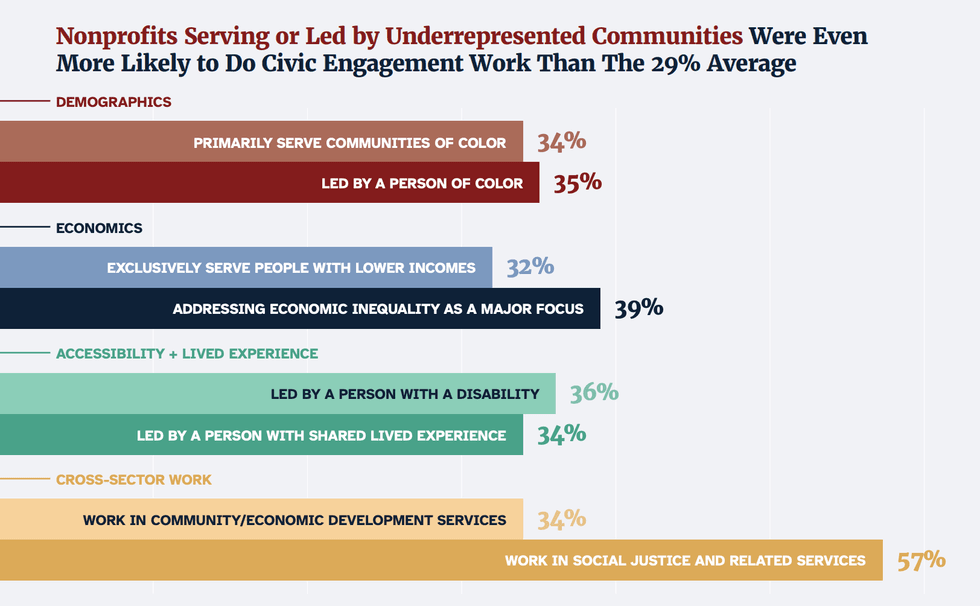

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift